This blog post by Sarah Duley is the sixth of a series of reflections by participants of the Food Leadership Programme, organised by Nourish from the 12th – 17th of July.

Are you a valued guest in the kitchen of the state?

In July I took part in the inaugural Food Leadership Programme run by Nourish. It was a fascinating, invigorating and exhausting week, during which we analysed many facets of our complex food system, digging deeper than I ever have before into the barriers and solutions that we are presented with in regard to food in our modern world.

Throughout the week we were presented with two different worldviews; one which is currently dominating the food system – ‘food as a commodity’ and one which is beginning to emerge and that we hope to champion – ‘food for people (and planet)’.

Probably partly due to my work with Soil Association Scotland on the Catering Mark myself, and others on the course, began to think about these two worldviews in terms of public food. Having begun working with public sector organisations through the Catering Mark only recently, the programme provided a timely exploration of the current system of food provision in the public realm.

One of the many activities during the course was a skype session with food innovators from across the globe. One of these innovators was Anya Hultberg of the House of Food in Copenhagen. This is a really exciting example of a city-led initiative to improve public food that was spearheaded by the City of Copenhagen itself. Started in 2007, it aims to improve the quality of meals offered by the City of Copenhagen to its citizens and to create a healthy, happy and sustainable public food culture.

The House of Food has become a vehicle for change, facilitating projects, providing consultancy, courses, training and communicating – all in the area of public meals. They have many years of experience in organic conversion of public kitchens, and in facilitating the process towards better public food, acting as agents of change on the kitchen floors of public kitchens across Denmark.

However, this isn’t something that happened overnight and Anya’s description of the House of Food and of the challenges they faced and the way they work, provided an inspiring example of change in public food. Anya described regular suggestions that their work be cut back to save money and consequently focussed a lot of energy into bringing politicians into kitchens to show them the unquestionable value of the work. She described difficulties in overcoming the automatic stigma and defensiveness encountered when suggesting a need for training, and emphasised the importance of allowing for peoples’ different interests and skills to be kindled. Local sourcing was mentioned as a continuing difficulty due to EU procurement regulations and Anya called for greater collaboration across Europe on this issue. Whilst challenges such as these of course exist, the House of Food gave us a flavour of the vision we have for food in the public realm in Scotland.

Perhaps partly as a consequence of this conversation, we collectively identified ‘public food’ as an area of strategic importance, and something we all, in our different ways and sectors of the food system, should focus our efforts on as ‘food leaders’.

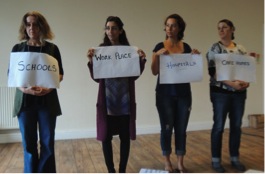

Towards the end of the week, we began to prepare for a presentation that would sum up (if possible!) our learning from the course, covering all major areas we had identified to focus on, including public food. In order to represent the current state of some areas of public food provision, we researched and came up with statements relevant to four different areas of the human life course where public food is currently provided. These statements were designed to be shocking and to make people think, but that doesn’t make them any less true.

The statements are listed below.

Schools

24 – 35% of school lunches are thrown in the bin

Why is adult onset diabetes rising in children?

Teaching shouldn’t be about managing the effects of sugar consumption

Workplaces

Food is seen only as a means to greater productivity

When is an hour not an hour? When it’s your lunch hour

When was the last time you ate with a colleague?

Hospitals

How is it possible for people to leave hospital sicker than when they were admitted?

Poor diet is related to 30% of life years lost in early death and disability

Hospitals don’t see food as medicine

Care homes

1000s of people in care homes are at nutritional risk

Malnutrition is estimated to cost the UK £7.3 billion per year

Are we giving enough consideration to the nutritional needs of the elderly?

Public food in Scotland should be explicitly for the people. It should be fairer, healthier and better quality. We shouldn’t be faced with these questions and facts.

There is an ever increasing urgency to enact change in all areas of public food – across the life course – ensuring public food represents public values and existing only to benefit people, rather than pockets.

All too often, however, procurement and financial barriers are cited by way of explanation of the current system of public food provision – and certainly they are very real barriers – but is this the reason we would give our children for the obesity crisis? Is our health worth so little to our government? Shouldn’t food nourish people in the long term and not just fuel them in the short term? Steps need to be taken (and it is possible to do so) to generate a new outlook on public food. New forms of hospitality need to be developed at all levels of society and our governments, the public food provider, should be leading the way.

There is growing public awareness of the food we eat and more people want reassurance that their food is healthy (i.e. not containing probable carcinogens like glyphosate), that their food is good for the environment (i.e. not flown for miles around the world), that their food comes from happy animals. Government, local government and health boards need to prioritise food as a key area in budget decisions – food is essential not marginal. Food should have strategic importance due to its wider impact on society so schools and hospitals shouldn’t be forced to operate on budgets which don’t take into account the true cost of food. Food provision should be given the same precedence as medicinal provision – in budgetary and procurement terms – why not?

The idyll of a local farm supplying a local school is admittedly hugely complex, but surely that is no reason not to work towards a better system of public food provision. A system that allows for farm-school interaction and supply should be championed and facilitated.

Throughout the Food Leadership Programme we explored food as a vehicle for social change. Within this, public food is just one avenue of endeavour – but what an impact it could have.

The definition of the adjective ‘public’ is “of or concerning the people as a whole” – and that is our mantra – food for people. Food as a commodity no longer has a place in our public sector food. As in Copenhagen, we would like to be welcomed and valued guests in the kitchen of the state.