The UK Government is currently pondering the future of the supermarkets watchdog – officially known as the Groceries Code Adjudicator, or GCA. The options on the table are to abolish the GCA altogether, leave it as it is, or extend its remit. Nourish calls for an extension of the powers of the GCA, alongside an increase in its resources. Food supply chains are currently characterised by imbalances of power, with a small number of large retailers able to dictate contracts to suppliers. These exploitative practices disproportionately affect smaller businesses. It is time the UK Government acts to bring some fairness and legality to the groceries sector.

What is the Groceries Code Adjudicator?

How it came about:

In 2008, the UK’s Competition Commission published the report of its investigation into the UK’s groceries market. It concluded that

“supply chain practices that transfer excessive risks and unexpected costs to suppliers, including through the use of retrospective payments and other adjustments to supply agreements, are sufficiently prevalent to cause concern”

In other words, the Competition Commission recognised that supermarkets were abusing their power and treating their suppliers unfairly. They saw this as a significant issue because it could ‘discourage suppliers from investing in quality and innovation; small businesses could fail and, ultimately, there could be potential disadvantage to consumers’.

They therefore decided to establish some code of conduct, which would be enforced by an ombudsman voluntarily set up by the industry. The former was established in 2009 as the Groceries Supply Code of Practices; the latter never materialised. As a consequence, the Groceries Code Adjudicator was created by an Act of Parliament in 2013 to oversee compliance of the Code.

The Code

The Code applies only to the 10 largest UK groceries retailers (who account for 97% of the UK groceries market). Under the Code these supermarkets are obliged to deal fairly and lawfully with their direct suppliers across a range of supply chain practices. The bad practices that are forbidden are the following:

- Retrospective variation of supply agreements and terms of supply

German starch factory – CC Flickr txmx 2

- Unjustified charges for consumer complaints

- Obligation to contribute to marketing costs

- Delay in payments

- No compensation for forecasting errors

- Payment as a condition of being supplier

- Not applying due care when ordering for promotions

- Not meeting duties in relation to de-listing

- Variation of supply chain procedures

- Payment for wastage

- Payment for better positioning of goods

- Payment for shrinkage

- Tying of third party goods and services to payment

The restriction to ‘direct suppliers’ is important. These can be wholesalers or manufacturers; but they are almost always middle-men, not primary producers. This means that indirect suppliers remain unprotected from bad practices such as the above-listed, so that excessive risks and costs can still be – and still are – passed on to them. Given the length and complexity of supply chains nowadays, it is safe to say that the vast majority of food businesses remain uncovered by the Code and therefore vulnerable to exploitative and unfair practices.

The role of the GCA

The GCA ensures compliance with the Code. It’s that ‘simple’. The GCA publishes guidance about how to understand specific clauses of the Code, it receives complaints from suppliers (and is required to protect their confidentiality), it proactively seeks to get supermarkets to collaborate and improve their practices, and when all this is not enough, the GCA arbitrates disputes between suppliers and retailers, and can launch formal investigations into specific issues if there is enough evidence to support the need for an investigation. It also has powers to fine a retailer for up to 1% of their annual turnover. How often do these ‘last-resort’ measures happen? Since its establishment in mid-2013, the GCA has been asked to arbitrate on 4 disputes – 2 of which are still ongoing – and it has launched and concluded one investigation.

It is important to realise that the GCA is not a big, fancy agency with a lot of staff and resources. Ms. Christine Tacon was the first person to be appointed Groceries Code Adjudicator. She works in this role 3 days per week with a small team made up of civil servants seconded to her by other Government Departments. The GCA’s budget is raised by a levy on the 10 retailers it regulates.

The Code and GCA’s impact so far

The establishment of a Groceries Supply Code of Practice and of a Groceries Code Adjudicator were two very positive steps to bring some fairness to supply chains. The GCA’s work has made a difference, although it has been strongly constrained by limited resources and the narrow scope of the Code.

Levels of understanding of the Code by suppliers has improved since the GCA was established, although proactive outreach and education remain necessary as some UK-based direct suppliers are still unaware of the existence of the Code, and almost half of direct suppliers outside the UK are unaware of it. Very good understanding is also still low (31%). It is important that suppliers understand the Code well enough so that they can be better equipped in their interactions with retailers and better able to defend their rights when the latter breach the Code.

Two cases addressed by the GCA have attracted media and public attention last year. First, after receiving reports of irregularities in payments to suppliers by Tesco, the GCA launched an investigation, through which evidence was  collected, reviewed, and eventually published in a report in the spring of 2016. This investigation found that even when a debt had been acknowledged by Tesco, on occasions the money was not paid for more than 12 months, with some amounts taking two years to be repaid (source). This report received extensive coverage in the press. Tesco was not fined, but was required to pay for the costs of the investigation. Remarkably, between 2015 and 2016 – possibly thanks to the GCA’s investigation – the number of issues with Tesco raised by its suppliers (as a percentage of all issues raised with the GCA) has dropped by 21%.

collected, reviewed, and eventually published in a report in the spring of 2016. This investigation found that even when a debt had been acknowledged by Tesco, on occasions the money was not paid for more than 12 months, with some amounts taking two years to be repaid (source). This report received extensive coverage in the press. Tesco was not fined, but was required to pay for the costs of the investigation. Remarkably, between 2015 and 2016 – possibly thanks to the GCA’s investigation – the number of issues with Tesco raised by its suppliers (as a percentage of all issues raised with the GCA) has dropped by 21%.

The second case that was brought to the public’s attention was abusive practice by Morrison’s (source). This retailer was found to have demanded 19 suppliers to pay substantial extra lump sums of up to £2m. In this case, the GCA did not conduct a whole investigation, as early evidence published by the press forced Morrison’s to admit to their wrongdoing and set things right.

In general, reports of issues have decreased but remain very high, as 62% of suppliers still say they experience issues with retailers.

In short, the GCA and the Code are not perfect, but we at Nourish believe that they are crucial instruments to tackle the imbalances of power that prevail in food supply chain and lead to exploitative practices, which are particularly damaging to small businesses. The GCA has been both a practical and cost-effective mechanism for enforcing the Code.

What next?

Despite all this, the UK Government was recently asking to be convinced of the value of the GCA and of the need for expanding its powers. In two parallel consultations that closed earlier in January, the Government was asking food industry stakeholders and any interested person how effective the GCA has been, whether to close it down or transfer its functions to a public body, and whether there is sufficient evidence mandating for an extension of the remit of the GCA – for example to include indirect suppliers.

Nourish submitted short responses to these questions (which you can find here). If you would like to read more detailed responses, see the excellent submissions from Traidcraft: on the performance of the GCA and on the case for extending its remit.

We want the UK Government to maintain and strengthen the role of the GCA. The Code should apply to the groceries sector in its entirety – thus including primary producers – and the GCA should be given the resources and power to enforce it.

The Modern Slavery Act (2015) established a principle that is very relevant to groceries supply chains as well. This principle can be summarised as ‘responsibility across supply chains’. The Act states that ‘commercial organisations must ensure that slavery and human trafficking is not taking place in any of their supply chains, nor in any part of their own business’. In other words, it is not enough that commercial organisations treat their direct employees well, they have a responsibility to ensure that workers across their supply chains are treated lawfully too.

Likewise, it is not enough for supermarkets to treat only their direct suppliers fairly and lawfully. This principle of ‘responsibility across supply chains’ should be enshrined in a reformed Groceries Supply Code of Practice. The principle of fair dealing and the list of forbidden bad practices should apply across the entire groceries sector, and retailers should be liable for practices further down their supply chains.

Another principle that we believe should be added to the Code is a principle of ‘fair pricing’. Retailers, wholesalers, and manufacturers should be forbidden from putting pressure on their suppliers to provide food and drink products for less than the cost of production. The aim of such a principle is that consumers’ money spent on groceries filters through to the primary producers, with no extra cost to consumers.

Unfair pricing is a significant issue in the groceries sector, in particular towards primary producers, and is not currently covered by the Code. This behaviour is not new, but has increased in recent decades due to very tough competition in the groceries sector putting downward pressure on prices.

British farmers produce 62% of the food that is eaten in the UK, yet they only get 9% of the Gross Value Added of the whole food and farming sector. This figure illustrates how much profit is made in long supply chains, but how little profit filters through to primary producers.

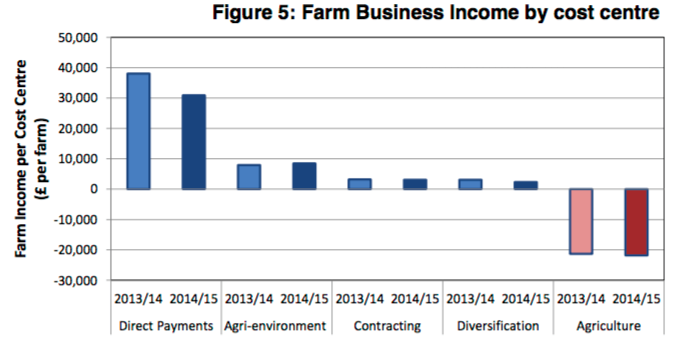

Retail prices have risen faster than farm-gate prices for many food items, and primary producers are sometimes forced to sell their produce at a loss. This reality was brought into broad daylight in the recent dairy crisis but exists in other sectors as well. The average Scottish farm does not make any profit from its agricultural output (see figure below) – and this is true for farms in the rest of the UK as well.

Source: Annual Estimates of Farm Business Income – Scottish Government, March 2016.

There is absolutely no reason why farmers and every business in the groceries sector shouldn’t be protected in the same way as supermarkets’ direct suppliers.

So is the UK Government likely to agree to extending the scope of the Code and the powers of the GCA?

That’s difficult to tell. The Government was seeking clear evidence of market failure from businesses’ internal information – such as an email exchange that demonstrates unfair treatment, accompanied with financial details of how this affected the business. The main problem, is that many farmers and small food businesses are worried that sharing such information will attract retaliation from the retailers, manufacturers, or wholesalers they sell their produce to. So it is uncertain whether the Government will receive a lot of clear evidence, and even if they did, they could still deem that there is not sufficient evidence of market failure.

Despite the suggestion in the consultation document that they may abolish the GCA, they are rather unlikely to choose this option. They could, however, decide to maintain the Code and the GCA as they are. After all, the UK Government is not really known for their appetite for regulation. Expert in Food Policy Prof. Tim Lang has previously described the UK Government’s Food Policy as “leave it to Tesco”, usually relying on market forces to deliver an optimal result for consumers (source).

So we will need to wait and see. If the Government deems the evidence they receive sufficient, legislation will be needed to amend the Code and extend the GCA’s role to cover the new Code. If they go down this route, we can expect another consultation in spring or summer about how to extend the remit of the GCA.

While we wait, let’s keep the pressure up. You can contribute – for example – by asking your MP to make a Parliamentary Question about the GCA or about a specific supply chain issue that worries you. Dysfunctional food supply chains are harming small businesses, farmers, and our environment, while profits are concentrated in the pockets of a few big players who too often hide their money in tax havens. A stronger GCA is no silver bullet, but it is an essential first step to improve accountability and fairness in food supply chains.