This blog post by Amabel Crowe is the first of a series of reflections by participants of the Food Leadership Programme, organised by Nourish from the 12th – 17th of July.

I piled into a car of strangers in Edinburgh on a rainy July Sunday, unsure of what was in store – but excited. ‘I think it will be quite relaxing, having the evenings to read and stuff’, one guy said, as we cruised north, leaving hectic city-lives behind for the week.

He was wrong. The proceeding five days were inspiring, stimulating, and wonderful, but I don’t think anyone would describe our jam-packed programme in the idyllic setting of Comrie Croft as relaxing. Nor should it have been: 32 individuals from different backgrounds discussing the massive and minutiae of the global food system. There were big questions to be answered, complex discussions to have, and a lot of work to do.

In the first of many group circles, Olga Bloemen from Nourish shared that the Indo-European root of “to lead,” leith, literally means to step across a threshold. But leadership could, perhaps should, be collective and humble. Alone maybe these words wouldn’t have meant a lot, but in the coming days Nourish really led by example for collective and humble leadership. A space was created in which each of us – disparate individuals – felt integral to the whole.

As we now return to different projects in different parts of Scotland, we not only have a treasure trove of information and analysis about the food system, but also the invaluable experience of having been in an environment in which we collectively crossed a threshold. Something I hope each of us can bring to others, as the movement for a fairer food system grows and grows.

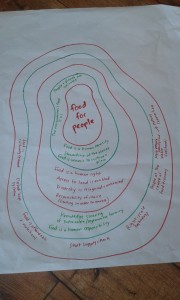

Because, a threshold needs to be crossed. The problems in our current food system are not rooted specifically in a single issue: not agricultural techniques, not food banks, not multinational corporations, not poor diets… Yes, all of these things, but the root (the smallest Russian doll at the core –one of the metaphors we used) is a mentality.

The idea that has somehow become dominant, and seeped like poison into every element of our food system, that food is a commodity.

Food sits alongside air and water as the most basic human necessity, fundamental to our survival. We need nutritionally rich food in order to live happy, healthy lives. How is it that food has become just another item to be traded on global markets?

Food that was recognised in 1948 as a universal human right, food that is so strongly intertwined with culture, food that is essential to our survival, remains inaccessible for too many people. In a world with intensive agriculture producing 4,800 calories per person, around 800 million

people are hungry. In Scotland twenty times more people now use food banks than in 2011.

Market forces are not only failing to feed people, they are starving the planet, and destroying lives.

Farmers in Scotland and the world over are encouraged to produce for global markets, perhaps for cattle or biofuels, rather than food for local people. With a focus on production, sustainability has been relegated out of the picture. The future looks bleak, with only 100 harvests left on British soil, such is the extent of degradation. As well as soil erosion, the new norm of input-heavy chemical agriculture, reliant on fossil fuels and ignorant of ecology, is also responsible for a loss of biodiversity. The number of wild animals on earth has halved in the last forty years.

Farmers, who are essential for our survival, are pushed to their limits. Unable to make a livelihood from their labour, plunged into debt, disconnected from those that consume their produce, and powerless before the inhuman demands of supermarkets and global corporations: is it surprising that the suicide rate among farmers and farmworkers is higher than average? Or that the average age of farmers is 58. It is neither an accessible, nor attractive, career path.

During the course, we balanced deeper learning on this depressing state of affairs with envisioning a different future. Learning from examples that already demonstrate an alternative, fairer, more sustainable food system. One that values producers, providers, and creates food fit for human consumption” ‘The future is here, it’s just not widely distributed yet’.

I would need pages and pages to describe and discuss the wide-ranging sessions that together formed a very special inaugural Food Leadership Programme. Suffice to say there were some amazing discussions, much collective learning, fatigue and hysterics, a most beautiful ceilidh, cooking on an open fire, and generally a lot of delicious, local food consumed.

Food is a powerful weapon for social transformation, and I think after the week at Comrie Croft, each of us feels a bit clearer about how to use it.

Piling out of the car in Edinburgh – on another rainy July day – I felt a different kind of excitement. One from the formation of new friendships, the anticipation of the path ahead with this amazing bunch of people; excitement from having a vision, rather than not knowing what was awaiting me. With some giddy goodbyes, we went our separate ways, but not for long.

Having crossed this threshold, committed to creating a better food system, with more tools and more alliances, this is just the beginning.