This blog post was originally a talk given by Keesje Avis at a webinar entitled “Scotland’s Response to the Climate Emergency” hosted by FoES and partners. See all the presentations here.

When talking and thinking about climate change mitigation, we tend to talk about numbers and in particular about carbon dioxide or CO2. And then, often in impenetrable silos of energy, agriculture and LULUCF – or whatever that means! Despite the fact that human activities criss cross these silos in many areas – such as food. Food produces up to 37% of emissions and yet we rarely discuss it at a policy level.[1]

The numbers are important. But the problem with numbers, reducing everything down to how many kilogrammes of CO2 equivalent we are saving or degrees of temperature that are rising, it is only part of the picture. The nature emergency is very real and connected to the climate emergency, as is the health and wellbeing of Scotland’s people and people around the world. And it is only by seeing these things in the round that it is possible to fully appreciate the trade-offs (because there are always trade-offs) and that is how we ensure some form of justice. This sole focus on carbon emissions is a major issue we have with the Committee on Climate Change’s report.

Of course we at Nourish like talking about food and, in fact, in this instance it is the perfect lens to start appreciating all of the interconnections and complexity of climate change.

Food is something we need every day. And for the lucky ones, enjoy multiple times a day. The Covid-19 crisis has brought home just how much more necessary food is than the latest fashion, the coolest gin, the smartest watch. Because it was all these other things that we were all consistently happy to spend money on and yet food needed to be cheap. For poor people. Why on earth should poor people eat cheap food? Why should their already compromised health be further complicated by increased pesticide and antibiotic residues, highly processed and laden in sugar and salt?

The pandemic has reminded us all about how our health and the health of our loved ones is paramount to our happiness and wellbeing. But once we go beyond the hand washing and social distancing of the current emergency, we have to remember that much of our health is based on what we eat. If we go back to the numbers, did you know that the NHS across the UK is responsible for over 5% of total UK emissions? [2] And those numbers don’t go anywhere near capturing the impacts of medical and other waste, or the fact that 3.5% of traffic on the roads is connected to the NHS.

So that begs the question – what is agriculture and land use for? Is it to provide financial returns for multinational faceless organisations and as a pawn in trade deals? Or is it to provide nourishment and fibre for us to be sustained, clothed and housed? Is wheat just a commodity or the key ingredient in our daily bread? Are cows simply burping machines providing us with excess calories or are they integral parts of upland systems that provide the most available source of iron when eaten in moderation? Did you know that 46% – that’s nearly half – of all adolescent girls in the UK don’t consume enough iron?[3] Are vegetables just the garnish on our plates to make it look pretty and then get scraped in the bin? Or are they fundamental to the good health of our guts and our emotional states?

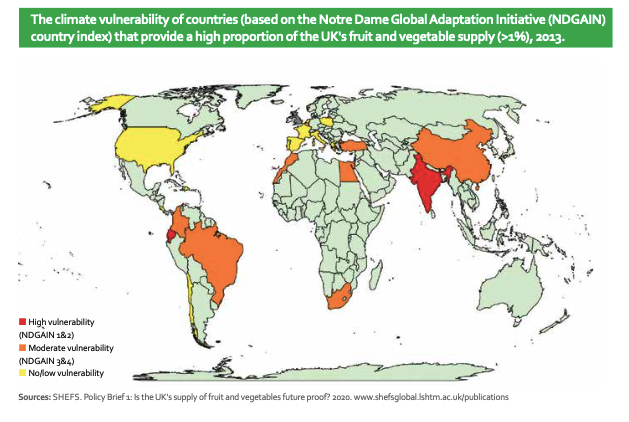

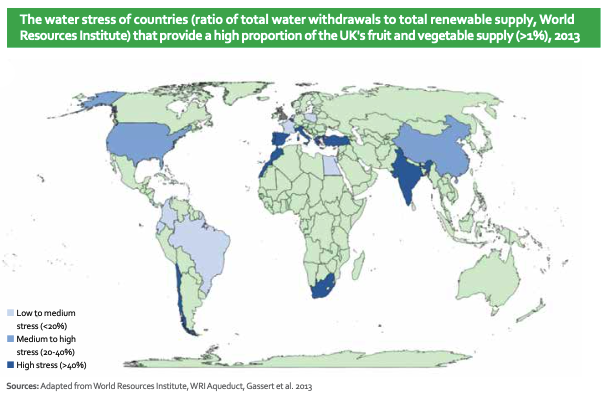

The question of vegetable production, consumption and its waste has huge implications on off-shoring our emissions and on justice. A third of the UK’s fruit and veg supply comes from countries particularly vulnerable to climate change and over half of our fruit and veg comes from countries facing high or extremely high levels of water scarcity. [4] Just thinking about the CO2e emissions does not encapsulate this vulnerability or current dependency.

Nor do CO2e figures take into account the plastic waste, the over nutrification of soils and water, the numbers of poor malnourished people growing this veg for us, who are in the vast majority black or brown. This colonial vision of exploitation needs to be properly confronted. We can produce wonderful and diverse veg here in Scotland with a bit of effort. But Scottish farmers do need help. Did you know that in 2018 there were 18% fewer vegetables grown in the UK? And in Scotland there was more veg grown for animal feed than human food in 2019.[1]

This joined up thinking – health, poverty, water and air quality and all the other trade-offs could be captured with an Integrated Food Policy for Scotland. Potentially, through the lens of a Green Recovery we have an even greater potential to bring these strands together. Because Green no longer just means recycling a couple of bottles and reusing a carrier bag. Now it means climate justice, racial justice, gender justice, poverty justice and tackling the nature emergency. Because we are part of one ecosystem, one planet, one community and food is the intersection of these strands.

So let me stop talking big pictures and provide some tactile suggestions:

- Create an integrated food policy for Scotland. Bring back the Good Food Nation and Circular Economy bills as they begin to look at these issues in a joined up way. In the meantime we are calling for a National Food Plan as part of the current Scottish Agriculture Bill. There has to be the recognition that the market does not provide the outcomes we need as a society when it comes to food. In fact, enshrining the Right to Food in Scots Law is what is needed to really tackle the inequalities in the system.

- Change the narrative on food. Stop the meat versus vegan argument because it isn’t doing anyone any favours and the issue is so much more nuanced than the media bites (excuse the pun). For example, while the number of people signing up to Veganuary increased by 1639.1%, sales of vegetables in January actually declined by 6.5% during the same period. The lack of vegetables in our diets is causing almost 21000 premature deaths in the UK every year (Food Foundation; 2020). And the vilification of farmers is only further pressurising a section of society who are battling with low incomes, huge debt, climate risky jobs and the knowledge that everything they have been told to do for the last 40 years is now wrong. Yes, there are huge improvements land managers must make but also remember that the current business models are built on structures put in place by our democratically elected policy and our common bowing to the motivation of cheap food and profit. We need to support farmers as we transition together to a better place. Make our farming, land and marine management about nourishment. Nourishing the soil and moving to an agroecological system means cleaner air, cleaner water, healthier ecosystems, and healthier people.

- Grasp the opportunity of local food. Nourish’s first ever strapline was “A Scotland where in every region we eat more of what we produce, and we produce more of what we eat.” The current exponential growth in demand for veg boxes shows that local is important to rural and urban communities in terms of access to food, availability of food, and diversity of product. All of which are key to resilience, because climate change will continue to interrupt international supply chains.

For me the nub of local is the heightened element of relationship. Good relationships are the basis of trust and so many of the issues with our current food system are about a lack of trust because everything has just gotten so big. I am referring to the relationship between producer and food citizen but also the one between feed producer and livestock farmer. This break down in trust across the food system will get so much worse if the trade deal as it currently stands with the US is signed.

At the moment Scottish agriculture as an industry is all about getting bigger, chasing economies of scale, a focus on more product needing more customers chasing more turnover because they have been consistently told farming is just another business. And yet farming is about food and land stewardship so must be about so much more than just money. Scotland may have a big land mass but it is small in population size which means a focus on money means a focus export, both nationally and internationally, and I include England in this simply because it is under a different agricultural policy.

We need a system in Scotland that doesn’t determine success in terms of scale but instead stimulates smaller processing facilities, smaller machinery, smaller farms, smaller shops and collaboration to create strong relationships and trust across the system. Part of the solution is to quite simply remove the minimum 3ha farm size outside crofting areas. This will be more inclusive of those who don’t have access to large tracts of land, inclusive of urban and peri urban growing, and inclusive of diversity from the crops being grown to the people growing them. That means more women, more young people and more people of colour being a recognised part of the system. We could also help their move to agroecological farming and lower GHG emissions by the government paying for organic certification costs. The WWF Scotland report “Delivering on Net Zero” (WWF Scotland, 2020)[2] shows that a systems change to organic farming in Scotland has the most potential for reducing GHG emissions – simultaneously it will also provide better habitats, reducing antibiotic use and pesticide use.

So to conclude, if we reduce climate change to just carbon emissions, reduce food to just calories, reduce agriculture to single commodities we miss out the fact we are human, complex and part of a beautiful dynamic ecosystem. It isn’t easy but our policies need to encompass this complexity to create a just future for us all.

[1] Nat Food 1, 94–97 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0031-z

[2] https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/healthcares-climate-footprint

[3] https://www.nutrition.org.uk/nutritionscience/life/teenagers.html?start=4

[4] https://foodfoundation.org.uk/publication/veg-facts-2020-in-brief/

[5] https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/scotlands-agriculture-can-cut-emissions-nearly-40-2045